Health Bill Would Threaten Care for Kids in Foster Care

The House passed American Health Care Act (AHCA) or Trumpcare would impose $834 billion in cuts and arbitrary caps to the Medicaid program and negatively impact the coverage, benefits, and care for all 37 million children covered by Medicaid. Unfortunately, although often overlooked, it is the hundreds of thousand of vulnerable children in foster care that are potentially the most threatened or harmed by the bill’s enormous Medicaid cuts.

This is particularly disturbing because foster kids are in the child welfare system because they have suffered from: (1) physical, emotional, or sexual abuse; (2) neglect or maltreatment; or, (3) are unsafe, which includes growing numbers of kids moving into child welfare due to parental drug use.

As the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) reports, in 2015, there were 671,000 children who spent some time in foster care. Furthermore, at any given time, there are more than 400,000 children in foster care and the average age of those children is 8.6.

These children need and deserve access to comprehensive physical and mental health care services, treatment, and our unwavering protection from harm.

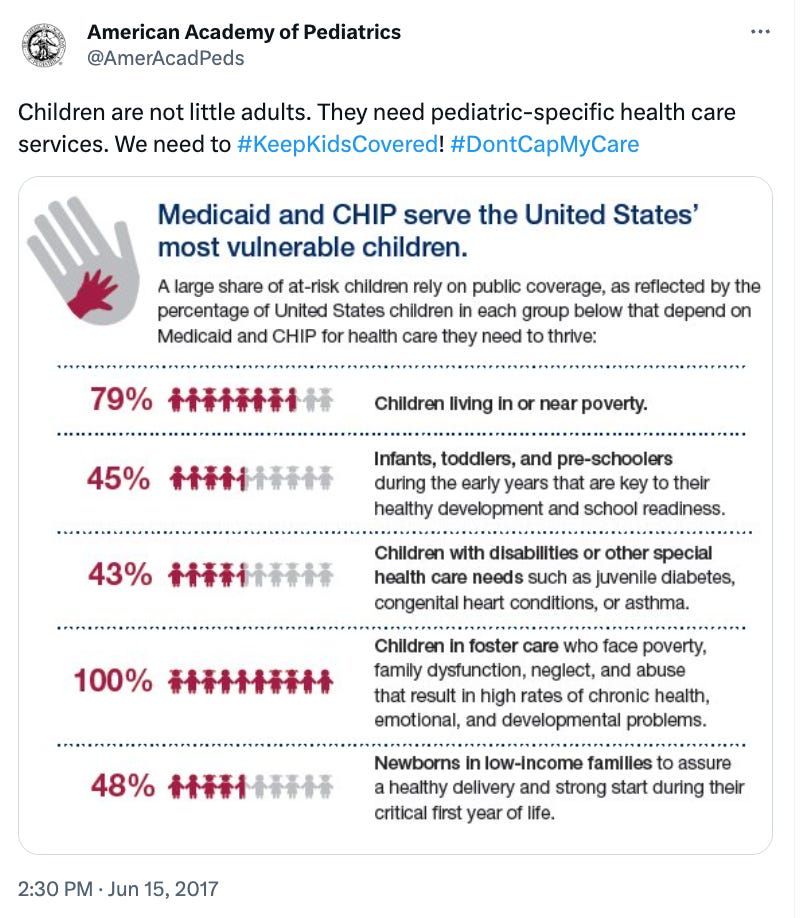

Most children in foster care qualify for Medicaid. Children and youth enrolled in child welfare’s Title IV-E programs, including foster care, guardianship assistance, and adoption assistance, are automatically eligible for Medicaid. Other children who do not receive Title IV-E assistance may also be enrolled in Medicaid on the basis of income, disability, or the state adoption assistance pathway.

Due in large part to the adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) they have, foster kids are far more likely to have developed toxic stress and greater health care needs. The American Academy of Pediatrics explains:

Toxic stress response can occur when a child experiences strong, frequent, or prolonged adversity, such as physical or emotional abuse, chronic neglect, caregiver substance abuse or mental illness, exposure to violence, or the accumulated burdens of family economic hardship, in the absence of adequate adult support. This kind of prolonged activation of the stress response systems can disrupt the development of brain architecture and other organ systems and increase the risk of stress-related disease and cognitive impairment well into the adult years.

The Center for Health Care Strategies (CHCS), in a report for the State Policy and Research Center (SPARC) at First Focus, adds:

The trauma associated with abuse and/or neglect, as well as removal from the home, has the potential to create a set of circumstances that may lead to challenging behaviors. Further, there is a subset of children who ultimately come to the attention of the child welfare system because their mental health needs outstrip the capacity of their families to manage. For these children, comprehensive and coordinated behavioral health care is critical to their health, wellbeing, and long-term outcomes, which are poorer than those of youth who have not had foster care experience.

Not surprising, a study published by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) found foster kids were far more likely to be diagnosed and treated for physical and behavioral health issues than children not in child welfare. For example, foster kids are 344 percent more likely to be diagnosed with attention deficit, conduct, and disruptive behavior disorders than children not in child welfare. The study shows foster kids also have higher rates of diagnosis for mood disorders (517 percent), adjustment disorders (644 percent), and anxiety disorders (461 percent). They are also more likely to have greater physical health needs, including blindness and vision defects (76 percent), disorders of teeth and jaw (108 percent), and developmental disorders (128 percent).

Recognizing the special needs and challenges that foster kids face, we must recognize the fact that we have much more to do to provide appropriate and adequate health care services to these vulnerable children. Shadi Houshyar, formerly with First Focus, explained:

We believe it is critical to meet the health care needs of all children in foster care. To do so, we must continue to monitor Medicaid expenditures for foster children, identify gaps in coverage, unmet needs, and barriers to access for certain subgroups, and develop cost-effective, targeted and appropriate services for this population. We need to invest in continued research on foster care health issues, including the utilization of care and the quality of care for children in foster care.

Fortunately, as the CHCS points out in a 2013 report, states are making great strides to improve the health coverage to children in child welfare. They have made effort to improve Medicaid by expanding home- and community-based services (particularly behavioral health services), adopting presumptive eligibility for children in child welfare to ensure more immediate access to physical and behavioral health services, and improving individual, group, and family therapy coverage. States have also adopted intensive case management, therapeutic foster care, medical passports, better monitoring and oversight of psychotropic medication use, and improved care through the creation of practice protocols for serving kids in foster care and the inclusion of skilled child welfare providers and specialists in their Medicaid networks.

Some of these initiatives have resulted in higher Medicaid spending to improve the care and services for these vulnerable children, while others have saved money by reducing over-treatment, such as the case of the use of psychotropic medications.

Regardless, by virtue of the fact that foster kids have more medical conditions and greater needs, their health care costs are higher. In a 2001 Urban Institute study by Rob Geen and others, they found:

States expended approximately $3.8 billion of Medicaid on foster children in FY 2001. On average, states expended considerably more on foster children — $4,336 per child — than on all nondisabled children enrolled in Medicaid ($1,315). Although foster children represent only 3.7 percent of the non-disabled children enrolled in Medicaid, they account for 12.3 percent of expenditures for the same group.

Nearly a decade later, the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) reviewed FY 2010 Medicaid data and reported:

These children accounted for. . .about 3 percent of nondisabled child enrollees. However, due to their high health needs and service use, Medicaid benefit spending for these children totaled $5.8 billion in FY 2010, or about. . .9 percent of spending for nondisabled children. . .

Medicaid benefit spending per child enrolled on the basis of child welfare assistance was $5,767, compared to $2,000 per non-disabled child and $14,216 per child under age 21 enrolled on the basis of disability.

In every report that looks at the health care needs of foster kids, all point to progress but continued shortcomings that deserve improvements. As MACPAC concludes in its review of the intersection of Medicaid and child welfare:

This is a complex area, but given the vulnerability of these children, MACPAC will continue to assess ways in which their care needs could be better addressed by Medicaid.

Nobody is talking about heading backwards, except Congress. In the House-passed bill entitled the “American Health Care Act” (AHCA), the legislation would impose billions of dollars in Medicaid cuts through the imposition of per capita caps or a block grant option that largely falls on non-disabled children, including foster kids.

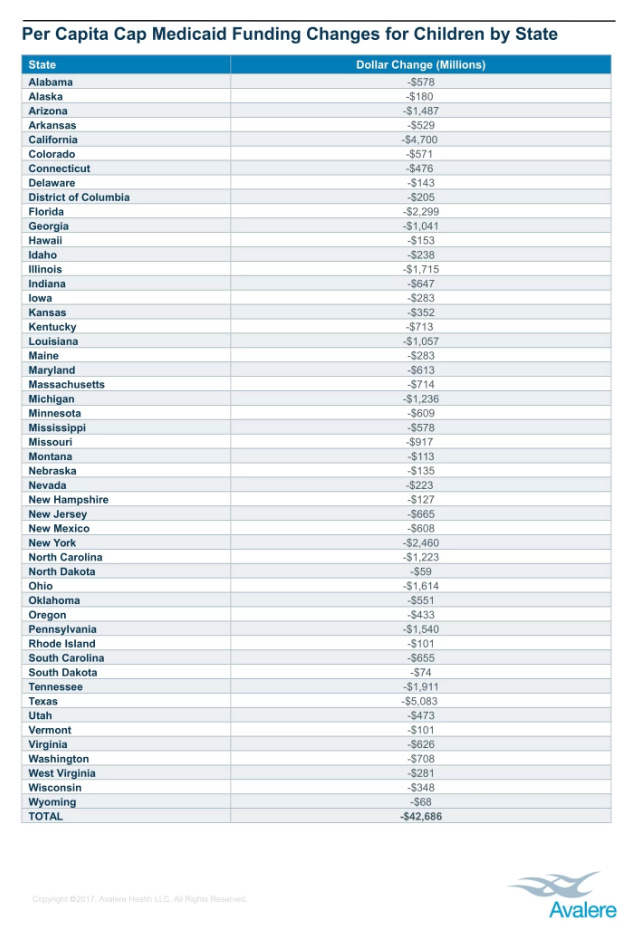

Avalere Health estimates the House bill would cut $43–78 billion out of health care for just non-disabled children in Medicaid. Those figures would be much higher if children with disabilities were also included.

According to Vernon K. Smith in a Health Affairs article entitled “Can States Survive the Per Capita Medicaid Caps in the AHCA?”:

The proposed shift in fiscal responsibility from the federal government to the states is so large, no amount of new flexibility could allow a response that wouldn’t include large state tax increases or severe reductions in coverage that would affect the medical services needed by the children, pregnant women, persons with disabilities, the elderly, and other adults now served by Medicaid.

Smith is right, but sadly, foster kids would likely be one of those groups targeted for these “severe reductions in coverage.” For example, under the MACPAC numbers, if a state were to be capped at an average of $2,000 per nondisabled child but foster kids cost an average of $5,767, the state would be more likely to cut or ration the coverage, benefits, and access to care and services of these higher cost kids to try to stay under the arbitrary federal caps or limits for children.

States might choose to cut Medicaid costs for foster kids in a number of ways. They could limit access to mental health services, reduce access to care by cutting provider payments, and eliminate intensive case management. Or worse, they could restrict optional eligibility coverage or even reduce the pathway to Medicaid coverage by reducing the ability of child welfare agencies to investigate reports of abuse.

Such steps could be devastating, and even life-threatening, to those who are the most vulnerable among us — children who have been abused and neglected.

The same is true for children who qualify for Medicaid under the optional state adoption assistance pathway, which allows states to provide Medicaid coverage to children who are receiving state-funded adoption assistance if they would not be able to be placed into adoption without medical assistance due to their significant health needs.

Such is the case of Nathaniel Rankin, who was born with a number of complex medical conditions. His parents have raised deep concerns about how Medicaid cuts and caps in the health bill before Congress could negatively impact his care and treatment. As Andrew Joseph reports:

The big fear for the Rankins is that Nathaniel could lose access to his care or have it interrupted with the potential Medicaid changes. It’s taken plenty of phone calls from them, and letters from their doctors, but with his coverage, Nathaniel has been able to get what he needs: the operation by the airway specialists in Cincinnati, visits to his team of doctors in St. Louis, regular appointments with occupational and speech therapists.

Joseph adds:

As they have thought about Nathaniel’s coverage, Kim and Rich have also wondered if potential cuts to Medicaid would discourage people from adopting children, especially those with intense medical needs. That would mean fewer kids like Nathaniel might find families like the Rankins.

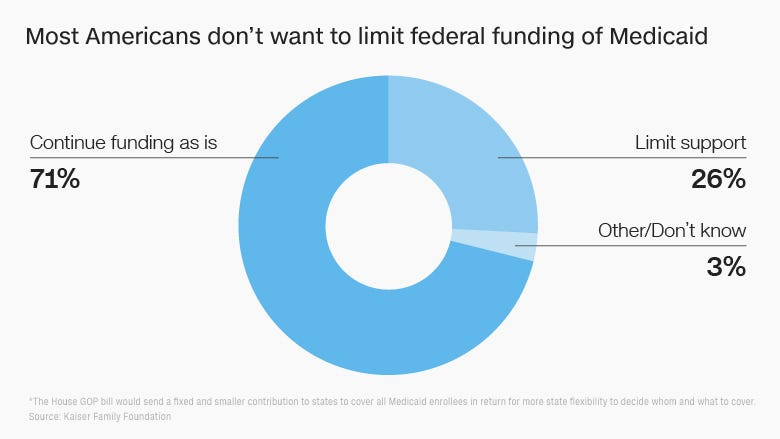

Sadly, states would have the same incentive to limit or ration coverage for millions of other children enrolled in Medicaid, including newborns, children with cancer, cystic fibrosis, spina bifida, autism, asthma, Rett Syndrome, and sickle cell anemia, or other higher cost populations such as pregnant women, people with disabilities, and senior citizens. Most Americans oppose such arbitrary Medicaid caps and cuts.

There is also the important provision in the Affordable Care Act that allows former foster youth to retain Medicaid coverage to the age of 26. The provision places youth aging out of foster care on par with their peers who are able to stay on their parents’ insurance until age 26.

Continued Medicaid coverage is critical for former former youth because, as a SPARC analysis points out, “youth aging out of foster care continue to experience poor health outcomes into adulthood, including high rates of drug and alcohol use, unplanned pregnancies and poor mental health outcomes.” However, unlike their peers who may be covered by their parents’ health plans, former foster youth would potentially be subjected to the Medicaid per capita cap or block grant limits and rationing in the House bill.

As a nation, we must be better than that. If nothing else, we should at least “do no harm” to vulnerable children. Now is the time to call your U.S. senators at 202–224–3121 and tell them to vote against the AHCA. The health and well-being of millions of Americans, including some of the most vulnerable among us, are at stake.

*****

If you would like to help ensure that children and their needs, concerns, and best interests are no longer ignored by policymakers and to protect our nation’s public schools from continued assault, please consider joining us as an “Ambassador for Children” or becoming a paid subscriber to help us continue our work on behalf of children.